Underground Resistance

Underground resistance is an open-ended, non-linear, interdisciplinary research project aiming to learn better resource management from fungi - the best resource managers on the planet.

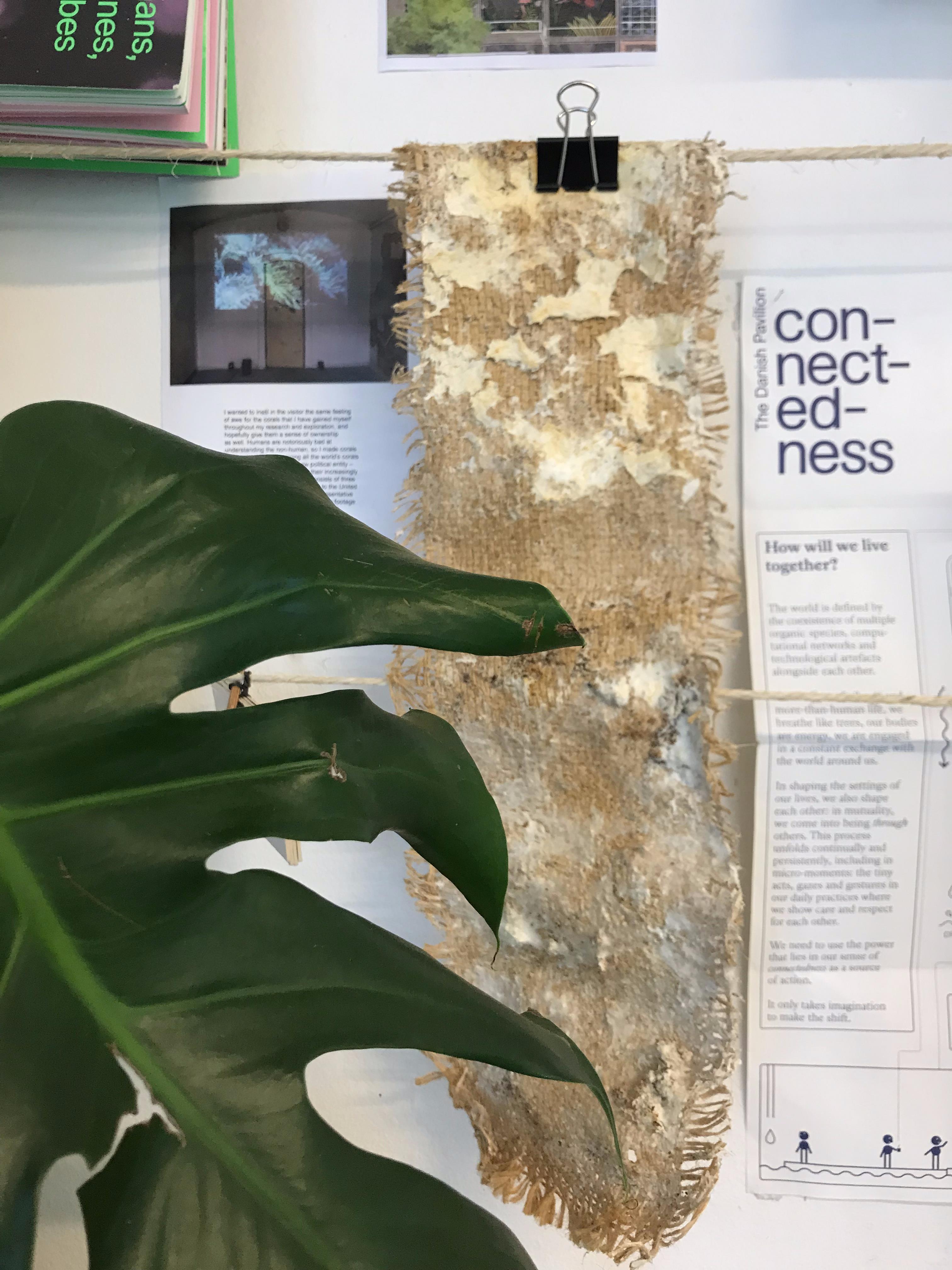

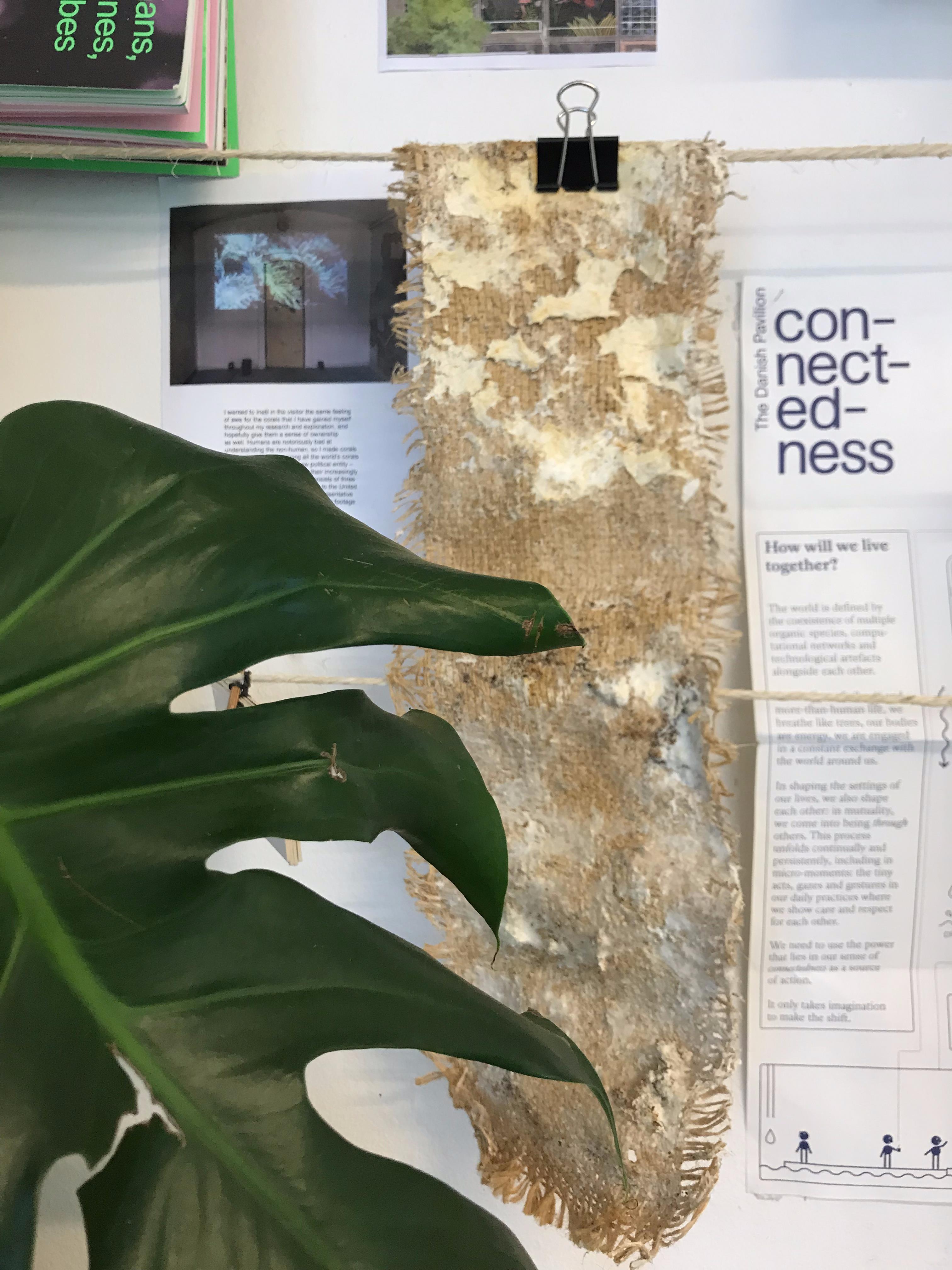

Underground Resistance exhibited at the Bergen School of Architecture

Type of project:

Artistic Research, Interdisciplenary, Critical Spatial Practice, Non-Extraction, Reuse, Alternative Biomaterials, Circular Economy, Prototyping, 1:1 Exploration, Master Thesis

Year completed:

2023-ongoing

Location:

The Anthropocene

Tutors:

Vibeke Jensen, Bernice Donszelmann, Alberto Altes

Artistic Research, Interdisciplenary, Critical Spatial Practice, Non-Extraction, Reuse, Alternative Biomaterials, Circular Economy, Prototyping, 1:1 Exploration, Master Thesis

Year completed:

2023-ongoing

Location:

The Anthropocene

Tutors:

Vibeke Jensen, Bernice Donszelmann, Alberto Altes

Fungi is the essential infrastructure of healthy ecosystems. They deconstruct dead matter, recycle, collaborate with the plants and animals around them and redistribute the available resources so that the entire ecosystem may thrive.

Interdisciplinary research into human production of trash and fungi in their natural ecosystems generated five topics of interest that were thus explored non-linearly through a process of making, re-making, and fungal modes of exploration.

The project unfolded (and keeps unfolding) gradually, expanding outwards in all directions with no clear end goal other than building strong relationships of mutual benefit to the living and non-living entities it encountered.

This approach transmuted trash into opportunities, generated multispecies spaces and initiated conversations and collaborations with companies working within circularity, food production, unconventional materials and even accounting. It cleaned mental clutter in a Swedish forest, dived into numerous waste containers and produced over 1.2 tons of a biomaterial made from only cellulose rich industrial waste and fungi.

Interdisciplinary research into human production of trash and fungi in their natural ecosystems generated five topics of interest that were thus explored non-linearly through a process of making, re-making, and fungal modes of exploration.

The project unfolded (and keeps unfolding) gradually, expanding outwards in all directions with no clear end goal other than building strong relationships of mutual benefit to the living and non-living entities it encountered.

This approach transmuted trash into opportunities, generated multispecies spaces and initiated conversations and collaborations with companies working within circularity, food production, unconventional materials and even accounting. It cleaned mental clutter in a Swedish forest, dived into numerous waste containers and produced over 1.2 tons of a biomaterial made from only cellulose rich industrial waste and fungi.

Resource management (waste)

The global phenomena and challenge of waste is common knowledge. Pictures of slums overflowing with trash, rivers polluted by toxic chemicals or dead animals full of cigarette buds and colorful pieces of plastic are commonplace. Well known is the threat of rapid climate change and the mass extinction of plant and animal life. So is the fact that humanity’s industrialized, capitalistic, extractivist and consumerist practices are to blame. At humanity’s current rate of waste production and its slow rate of change, the future looks destined for ecological (and human) collapse, which is why this project aims to learn better resource management from the non-human rather than the human.

Fungi

The greatest recyclers and resource managers on the planet are the members of the fungal kingdom. Without them, organic matter would just be piling up and humanity would live in strange coral reef-like structures of dead trees and other organic waste just laying around in piles. Because of fungi, waste does not exist in nature.

Fungi are a varied group of species. Some break down and recycle dead organic matter so that their constituent nutrients are ready to be reused once more, while others collaborate with the species around them to ensure the resources are distributed well, such that the entire ecosystem may thrive. They do so by connecting to the roots of plants, aiding their search for nutrients, but also to let them communicate with other plants through their underground fungal network.There are fungi that live in between skin/plant cells and in digestive systems, essentially cohabiting space with their hosts and doing everything they can to protect them from external threats, and there are even fungi that break down living organic matter, effectively testing the resilience of the ecosystem and training it to evolve.

The success of fungal ecosystems become evident when looking at their 850 million year old history of sustainably thriving, expanding and collaborating, as opposed to humanity’s meager 250 thousand (of which the last 10 000 years have been increasingly devastating to the planet).

The Underground Process

Early anthropological research into the ways humans produce and deal with waste combined with research into fungal behaviors and roles within their ecosystems provided the foundation that the project grew from. From this early research five widely different topics of interest were generated, that were then explored concurrently following a specific set of rules based on fungal modes of exploration:

- Build on existing knowledge to explore new landscapes

- Take no ownership. Be the mediator of the process, not the creator

- Let knowledge discovered in one line of research influence other lines of research

- All knowledge and materials absorbed into the process must be digested before being built upon

- All knowledge must be made available for others to build upon later

- Work non-linearly and process oriented, not linearly and goal oriented.

- Accept all weird paths and dead ends that may appear

- Let the process be open-ended. Allow it to unfold and expand indefinitely, and extract interesting results from it as it grows, without stopping it

Conversations

Conversations- Natural Material Studio, DK - a design and research studio exploring novel natural materials

-

Resirqel, NO - an interdisciplinary concultancy company specialising in reuse

-

Mycela, NO - a design and research company specialising in mycelium materials

- Norwegian Trash, NO - a design studio reusing/reshaping ocean plastics

- Hella Sopperi, NO - a gourmet mushroom farm

- The Kombucha, NO - a kombucha brewery

- Gruten, NO - a mushroom farm (permanently closed)

Collaborations

- Hella Sopperi, NO - a mushroom farm North of Bergen providing near unlimited amounts of SMS (Spent Mushroom Substrate) a waste material from mushroom production

-

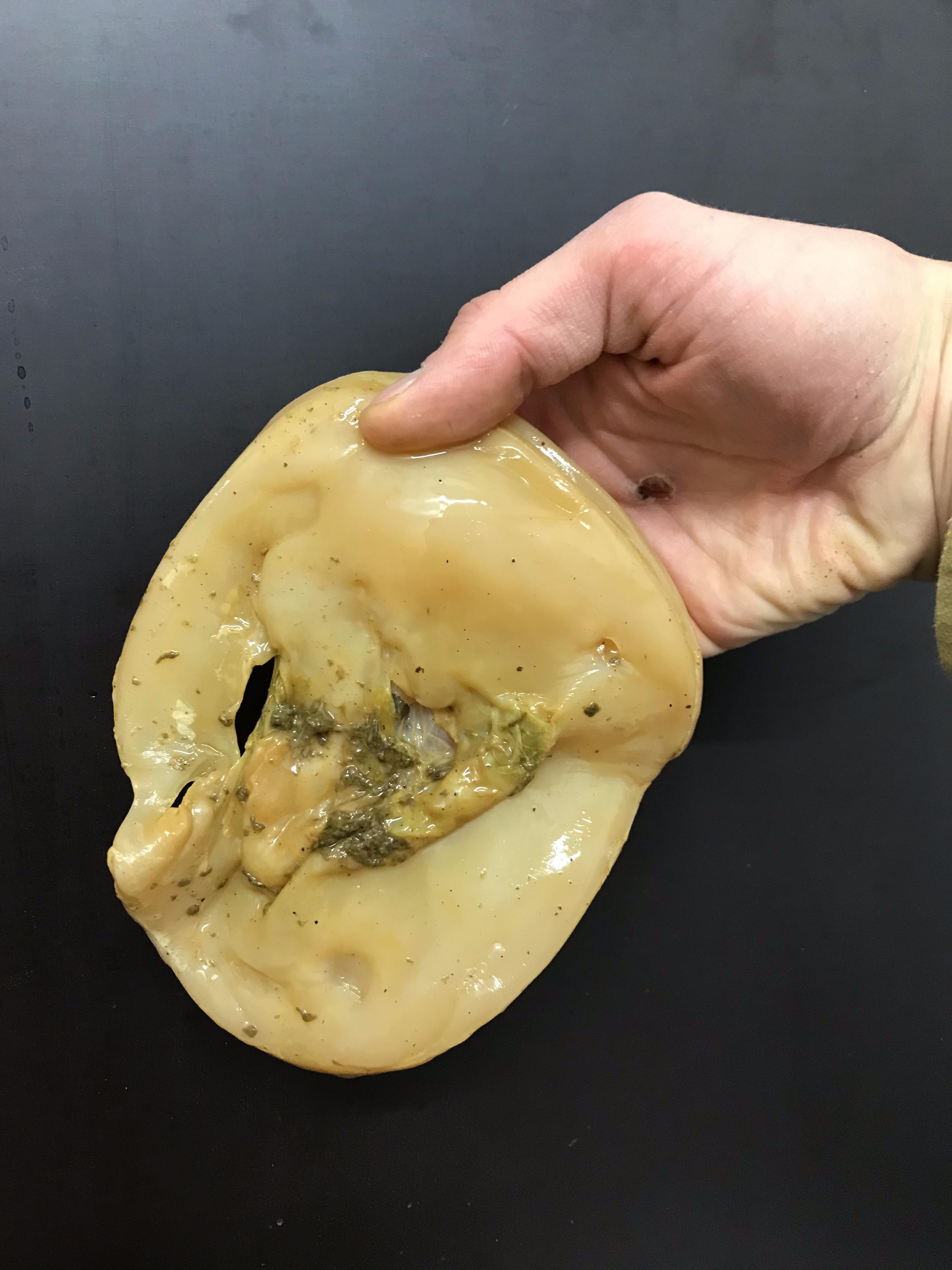

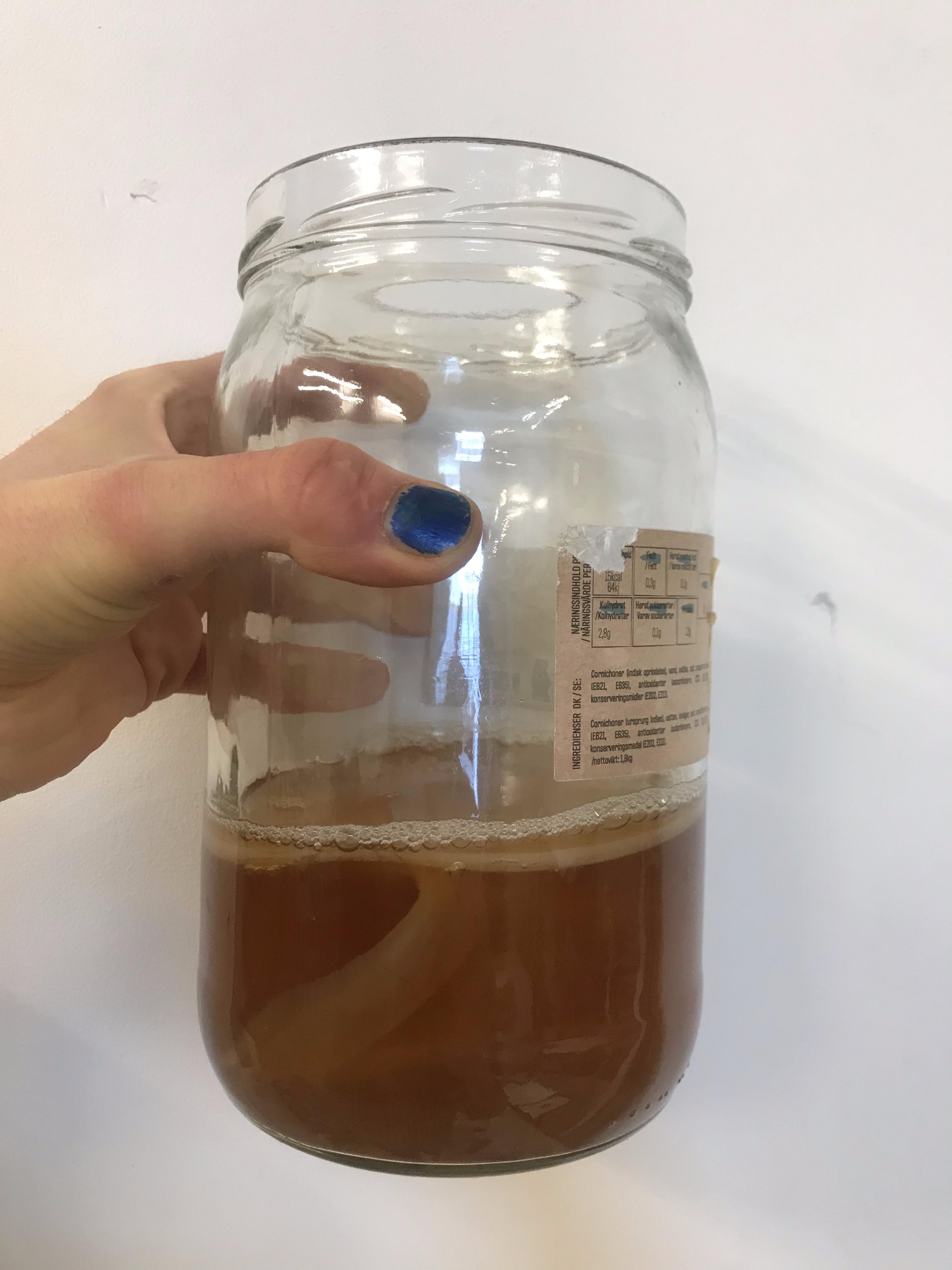

The Kombucha, NO - a kombucha brewer in Bergen providing 60-70 kg of SCOBY (Symbiotic Compound Of Bacteria and Yeast), a gelatinous waste product from kombucha brewing

-

PWC, NO - an accounting firm providing coffee grounds from their coffee machines

-

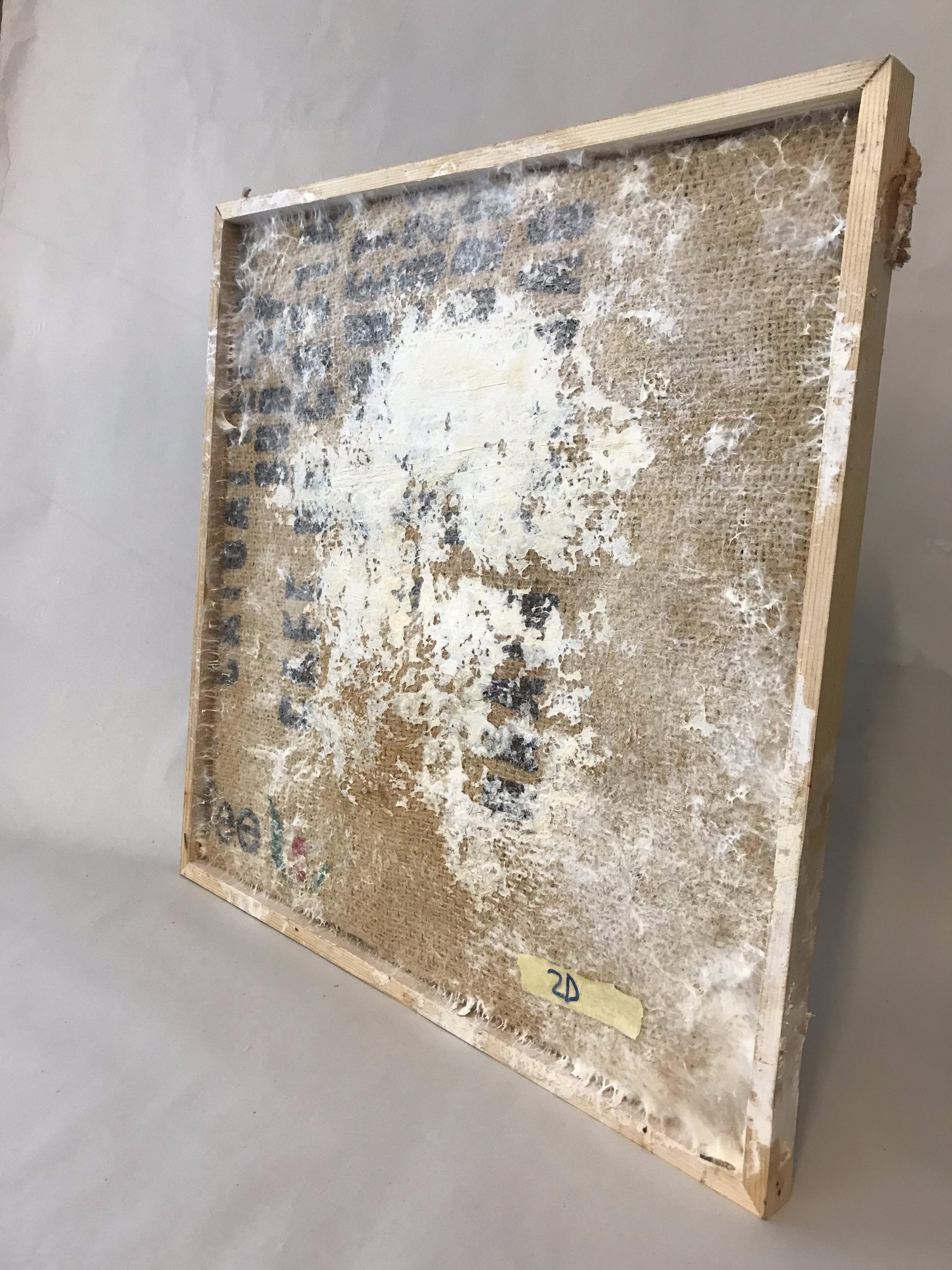

Bergen Kaffebrenneri, NO - a coffee roastery providing jute bags

The five topics:

- Fungi as process - Can fungal roles and behaviors within natural ecosystems be translated into a guide for how to interact with materials and one’s surroundings? What kinds of discussions/suggestions/alternatives would such a guide generate?

- Fungi as material - Can bio-based materials made with industrial waste and fungi become a viable alternative to current non-recyclable and non-biodegradable materials? What are the opportunities for producing such materials at and around BAS?

- Fungal landscapes - Do fungal spaces have something to teach us about the way we organize our spaces? We know what a Roman/Modernist/Aztec/etc. doorway looks like, but what about a fungal doorway?

- Fungal meditations - Can we learn to think like fungi? Can exercises of extreme empathy with the non-human teach us to be better custodians of our resources?

- Homo Mycologicus (the human acutely aware of fungi) - What would it mean to live more attuned to the microbiome of the human body (on the skin and in the gut), and help it thrive for the benefit of both entities? Could learning to share our bodies with the non-human make us better material managers?

Provisional results of the Underground Process

- Translating fungal roles and behaviors within natural ecosystems into principles for resource/material management and how to approach the world, opened up interesting discussions on co-production, cooperative ownership, co-housing, diversification of society, self-organization, deregulation/re-regulation of economies and the need for a circular economy.

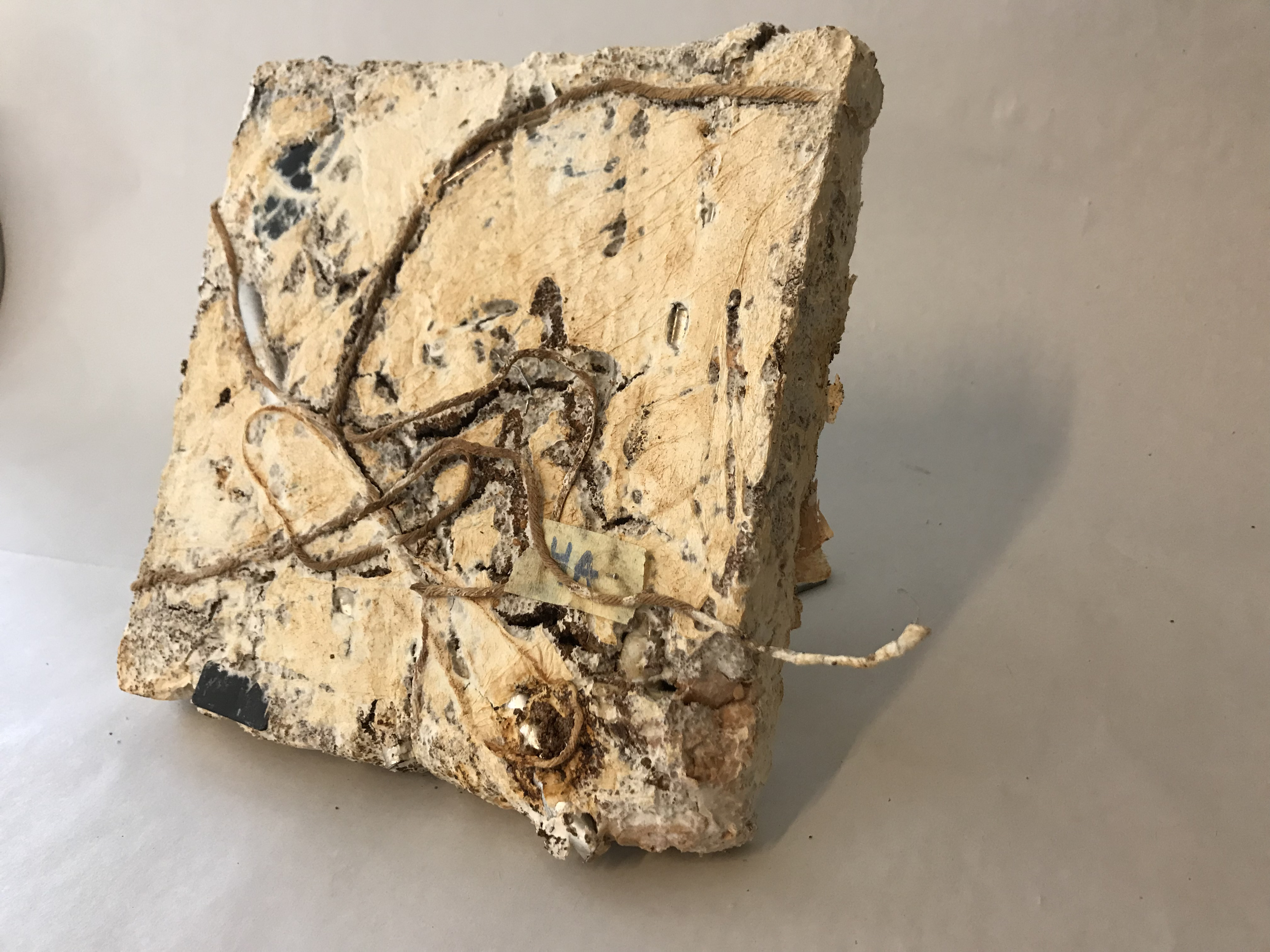

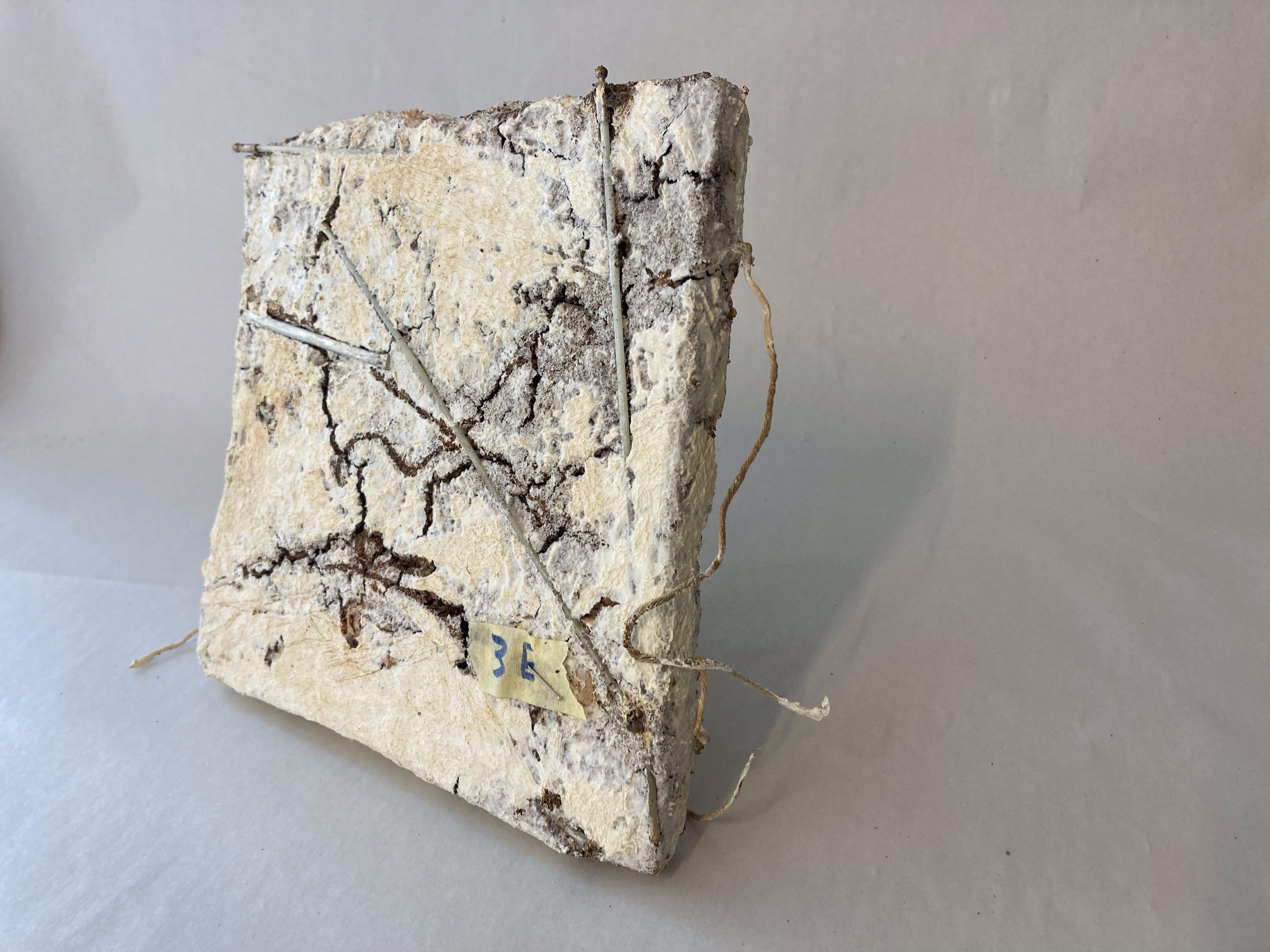

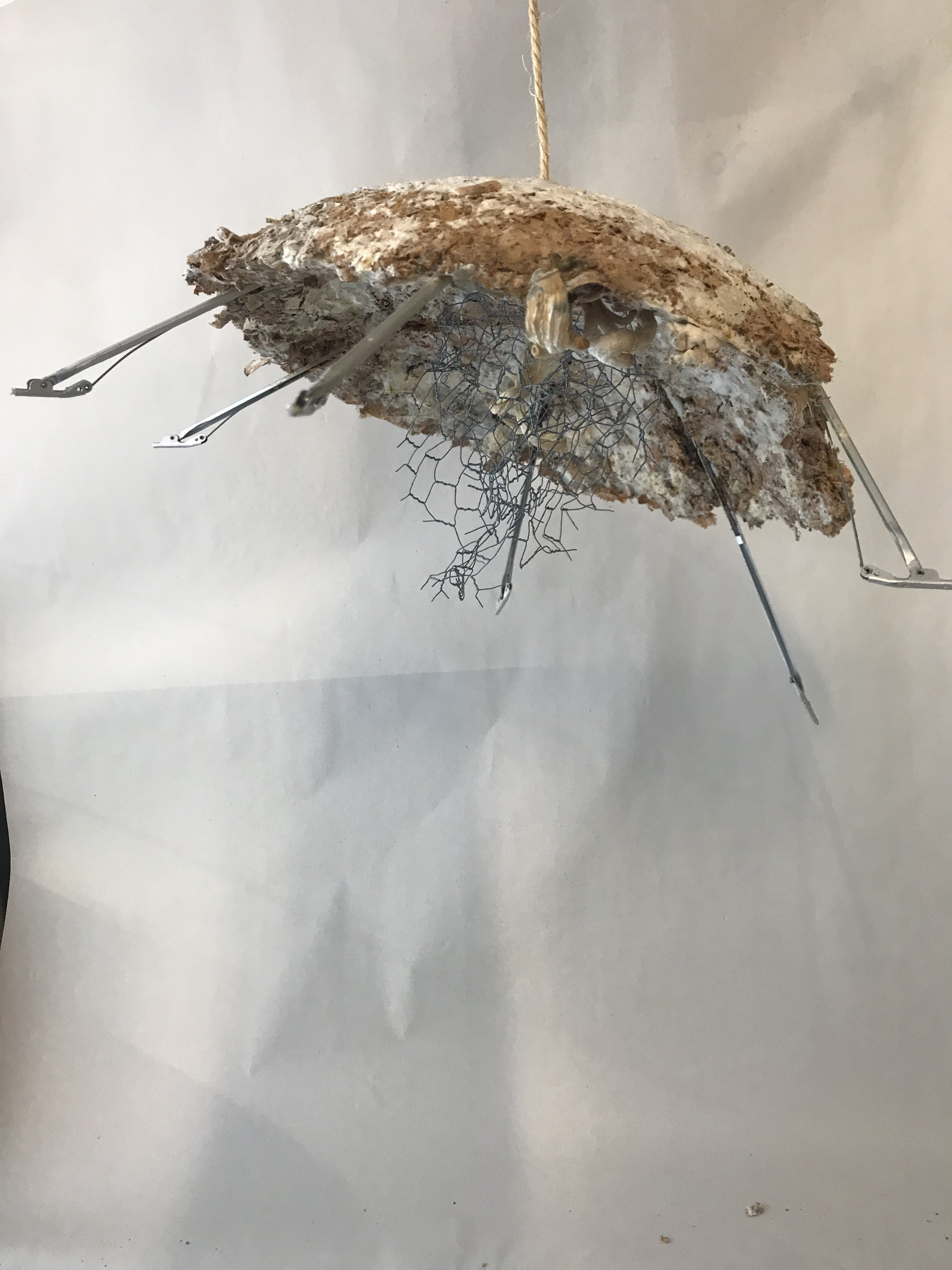

- The properties of composite mycelium materials were explored by combining local waste materials (leaves, textiles, asfalt, sand, gypsum, metal, a broken umbrella, cardboard, etc.) and mycelium (the root system of fungi) as a binder. This material has great acoustical, insulation, and fire resistant properties. It is non-toxic, odorless, fully compostable, lightweight and durable. If treated right, individual pieces can fuse together, eliminating the need for mortar or screws, which also makes decomposition easier at the end of its lifecycle. During the project the material was explored, experimented with, and shaped into bricks, bowls, acoustical plates, large scale structures and lampshades.

- About 1.2 tonnes of Spent Mushroom Substrate, a waste product of the aforementioned mushroom farm, was successfully used in building large mycelium structures. As far as the literature goes, it's an innovation of the project.

- A strong, translucent, biobased leather-like material was produced as a byproduct of Kombucha, a fermented tea that is beneficial for human gut health.

- Edible oyster mushrooms was grown from non-recyclable cardboard waste.

- Empathetic exercises and meditation experiments led to the creation of fungal design principles used to shape the exhibition space.

- Experiments in improving the human microbiome led to a stronger immune system and healthier lifestyle based on fermented foods and cold showers, which support all other processes.

- Experiments in meditation and cleaning information junk from the mind proved to improve focus, mental capacity, better sleep and less stress, which also supports all other processes.

- And an understanding of resource management, both intuitive and technical, is deepening